How to ship certificates to buyers

In the course of one week, a correspondent received two poorly-packaged purchases and I received one. My purchase was a one-of-a-kind specimen damaged in transit. The eBay seller who sold the item was not a rookie. I decided not to complain because I paid so little for the certificate.

My correspondent, though, had paid serious money for his two rarities, one from an eBay seller, and one from a major dealer. He DID complain and both sellers made right on their transactions.

We commiserated with each other, but we wondered why any seller, rookie or long-time pro, would risk losing customers over pieces of cardboard. What do those people think they’re saving when they fail to protect paper collectibles during transit?

It seems amazing, but I can only find three engraving companies that used logos to identify their products. The hands-down most-used logo was this one from the Goes Lithograph Company. This tiny oval logo appears in the bottom left corner of almost all the company’s lithographed certificates. Other companies were more skilled at engraving and printing, but none used logos to support their corporate identities like Goes. It would do well to note that Goes is still in business while all the others are gone! (Original size about 0.25 inches wide.)

It seems amazing, but I can only find three engraving companies that used logos to identify their products. The hands-down most-used logo was this one from the Goes Lithograph Company. This tiny oval logo appears in the bottom left corner of almost all the company’s lithographed certificates. Other companies were more skilled at engraving and printing, but none used logos to support their corporate identities like Goes. It would do well to note that Goes is still in business while all the others are gone! (Original size about 0.25 inches wide.)

Maybe they have reasons. Maybe they simply don’t realize the business they’re in. Maybe they need to review how to ship certificates through the mail.

First, do no harm. In that respect, shipping collectible paper is like surgery: Ill-informed sellers don’t seem to realize they can do more damage with poor packaging than collectors will do any time thereafter.

Yes, dealing with the mail can be difficult. You have no control over how people will handle your packages during shipment. You do, however, have significant control over how you can to minimize the possibilities of damage.

Understand your goal. No matter how obsessive you may be about pinching pennies, your goal is NOT to save money on postage. Your goal is to ship paper collectibles without damage. If you're trying to save money on postage, charge more.

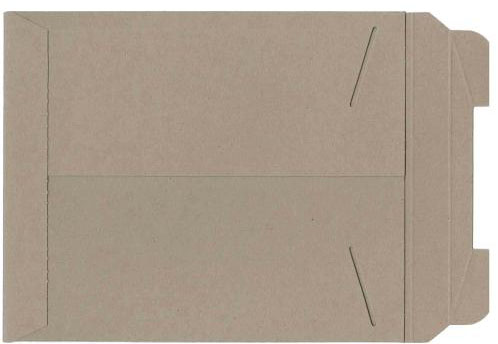

Use stiff packaging. I almost feel stupid mentioning this obvious solution. However, I receive many packages with essentially no protection.

Rigid mailers offer the easiest and cheapest protection. Many companies sell them, all with nearly identical designs. They are constructed of heavy kraft or white paper. They are available in a huge ranges of sizes. Some are large enough to ship full-size newspapers – flat!

I see no reason for professional sellers not to use rigid mailers. They are cheap. They are easy to find. They protect paper collectibles extremely well.

368 New certificate varieties since June

|

June

letter |

This

letter |

| Number of certificates listed (counting all variants of issued, specimens, etc.) |

23,000 |

23,435 |

| Number of distinct certificates known |

17,444 |

17,812 |

| Number of certificates with celebrity autographs |

1,703 |

1,720 |

| Number of celebrity autographs known |

347 |

348 |

| Number of railroads and railroad-related companies known |

26,043 |

26,117 |

| Number of companies for which at least one certificate is known |

7,156 |

7,385 |

| Serial numbers records |

85,570 |

93,355 |

Here is a typical rigid mailer sold by Uline.

European shippers use inadequate variations of these mailers. They have ordinary paper on one side and chipboard on the other. While an intriguing design, the mailers are too light for certificates. They offer little protection for certificates and collectible documents. They can be made to work if stiffened with additional pieces of cardboard or chipboard.

The United States Post Office offers free mailers for use with Priority Mail. By themselves, they are also too flimsy for shipping certificates. They, too, can be made useful when stiffened with properly-sized pieces of cardboard.

Home-made packaging. If you need to ship only a few certificates, or if you need to ship oversized bonds, you can make your own mailers. Simply sandwich certificates between two pieces of corrugated cardboard. Orient the corrugations at 90 degrees to each other and the packaging will become very stiff.

You can also make mailers with ordinary 9x12 kraft envelopes with two pieces of cardboard inside.

Do NOT use manila folders for stiffening. They offer no resistance to bending or folding.

To fold or not to fold. Stocks and bonds were specially printed so owners could fold them for easy storage in banks and safes. They were meant to be folded.

If you are shipping certificates that have been stored unfolded for a long time, then ship them that way in rigid mailers.

However, if certificates have been stored folded, I don’t see any problem shipping them that way. Make sure, however, that you tell your buyers beforehand. Inexperienced collectors often freak out when they receive folded certificates.

Poly bags. I don't know why anyone ships certificates in poly bags. And yet, about half the collectible documents I receive are shipped in poly bags. In my opinion, poly bags have no purpose except to keep pieces together. The biggest problems with poly bags are that people insist on closing them with tape. Nothing is going anywhere inside of an envelope. When customers try to open poly bags, tape becomes a potential implement of damage.

I advise to never remove tape to try to save a poly bag. Cut bags open and discard them. If you insist on removing tape in order to save poly bags, go ahead. But, (with deference to recyclers) let tape get stuck to a single certificate and your economic loss will offset the value of every precious poly bag you’ve ever saved!

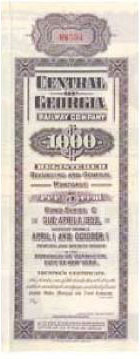

Never, never, never ship certificates in soft packaging. Padded envelopes, bubble-envelopes, and bubble wrap are terrible for shipping paper. Padded envelopes offer no protection against folding.

One of the surest ways to kill a certificate is to ship it in bubble wrap. DON'T DO IT!!

One of the surest ways to kill a certificate is to ship it in bubble wrap. DON'T DO IT!!

Let me repeat NEVER, NEVER, NEVER, NEVER, NEVER, NEVER ship certificates in soft packaging!

A few weeks ago, I received a collectible engraving in a bubble envelope. While the dealer considers herself a “dealer”, I suggest her greatest experience, sadly, is pinching pennies. During transit, some numbskull set a heavy package on top of the bubble envelope. Now I have a very rare print with about a hundred unattractive bubble impressions.

(In case you’re wondering, yes, the illustration above is genuine. I took this picture when a bond arrived, also packaged in bubble wrap. Like my rare print, this bond is heavily wrinkled with bubble dents.)

Mark the outsides of packages. If you ship many certificates, buy a self-inking rubber stamp that says something like “DO NOT FOLD” or “DO NOT BEND.” Be inventive! Use bright red ink. Be liberal in your application. Believe it or not, ink is actually cheaper than replacing damaged certificates and infuriated customers. Rubber-stamp messages may not prevent anyone from folding your packages, but they cannot hurt!

Never-discussed cancellation type

Tiny, rarely-seen monogram from the American Bank Note Company, only about 0.2 inches wide.

In the last few months, three different collectors reported certificates that had been issued, signed on the backs and legally transferred, but not otherwise cancelled in any manner. I did not ask, but I strongly suspect that all three bought their certificates under the impression they were “uncancelled.”

But are those certificates really uncancelled? It comes down to how we define cancellation. In my opinion, if a negotiable document has been rendered non-negotiable by any method, it is has been cancelled.

Some people might say my approach is overly strict. They might be right, but I argue for simplicity itself. I suggest looking at documents from the viewpoints of original issuers. If original issuers could have examined those certificates and justifiably declared them “non-negotiable”, then they must have been cancelled.

Prior to about the 1930s, the transference and cancellation of negotiable securities was complicated and involved passage through several hands. First, owners or their attorneys were supposed to sign the backs of certificates. Other individuals often witnesses those signings and also signed or initialed certificates. Certificates were then shipped back to company headquarters and sometimes marked along the way by bank or trust company clerks.

Once back in company control, clerks usually cancelled certificates in some manner and finally pasted them back onto their matching stubs in original certificate books. Evidence suggests that mistakes and oversights were fairly common, almost certainly exacerbated by hot summers, cold winters, and busy expansionary periods.

By the 1930s, clearing houses and trust companies streamlined the process for the larger companies and took over much of the burden of recording stock and bond transference and ownership. By offering increased redundancy and better processes, those service companies dramatically decreased cancellation errors.

This monogram from the American Bank Note Company is a quintessential example of corporate and personal monograms popular during the 1890s. Note the letters ABNCo in the design. (The “N” is well-hidden, using the strokes of the “A” for part of its shape.) Although most collectors are familiar with this tiny monogram, it actually appears extremely few times on railroad certificates. (Original size about 0.25 inches wide.)

This monogram from the American Bank Note Company is a quintessential example of corporate and personal monograms popular during the 1890s. Note the letters ABNCo in the design. (The “N” is well-hidden, using the strokes of the “A” for part of its shape.) Although most collectors are familiar with this tiny monogram, it actually appears extremely few times on railroad certificates. (Original size about 0.25 inches wide.)

I imagine that the cancellation of bonds would have been very similar to stocks, at least among the largest and most stable of railroad companies. It appears, however, that a huge percentage of bonds were never fully redeemed outside bankruptcy courts. It is understandably hard for collectors to determine whether some bonds were fully cancelled or not.

To get back to the point at hand, what about stock certificates that were transferred, but lack obvious cancellation?

In my opinion, certificates should be considered “cancelled” if there is documentary proof that certificates are no longer negotiable. To me, they are “lightly cancelled” for sure, but still cancelled.

This situation seems clear to me, but I can imagine a grayer area of concern. What about a stock certificate that was legitimately issued, never signed on the back, and yet shows evidence it was pasted back onto a stub in a company stock book? Was it cancelled?

An original issuer might have argued that paste shows intent for cancellation. However, is paste alone proof of cancellation? Without any signatures, I don’t think so. For our purposes as collectors, I’d call such a certificate “uncancelled.”

What is the economic implication? At this point, I can detect almost no price differences between uncancelled certificates and lightly-cancelled ones. In fact, the market for collectible certificates is so thin that I continually see examples of “upside-down” pricing – i.e., higher prices for cancelled certificates from one source than uncancelled certificates from another. Ultimately, I think the situation will change, but change is not yet on the horizon.