Why not include utilities?

Tunnels, bridges, and utilities are the types of companies that have caused the most discusion about whether to include certificates in this project. The simplest and most logical answer I can give is, "Certifictes from tunnel, bridge, and utility companies belong in this project when involvement in railroading appears in their corporate names." If they lack such indication, they don't belong.

The rule

Discussions about these three industries have consumed an enormous amount of time., hence this rule:

I will include certificates from tunnel, bridge, and utility companies in this database IF AND ONLY IF one or more railroad keywords appear in their corporate names,

Keywords will appear in their names something like this:

- XYZ Railroad and Tunnel Company

- XYZ Bridge and Railway Company

- XYZ Power and Street Railway Company

The rationale

The most difficult of all industries to deal with has been utilities. This is because huge numbers of utilities began as street railway companies. Even after gaining most profits from power generation, many utilities operated street railways for some time. Still, the overwhelming majority chose NOT to indicate their involvement in the transportation industry with their company names.

Many references to railroad companies and street railways include utilities among their listings. My goal, however, is NOT to record every utility that ever had an interest in, or even operated, a street railway. We need to remember:

- utilities operate as an industry that creates profit from selling power,

- railroading is an industry that creates profit from providing transportation.

Yes, railroading and electricity production overlapped for extended periods in many locations. That is not in dispute.

Nor is it in dispute that this is a one-man project. Time is the primary limiting factor for what I can accomplish. Corporate history research is terribly time-consuming and beyond the purpose of cataloging stocks and bonds. Anyone who tackles corporate histories will run into information sources that are incomplete, contradictory, and rife with arguable "facts" and outright guesses. Therefore, determining whether any particular "utility" would qualify for inclusion based on whether it operated a street railway for a specific period of time can be very difficult to confirm.

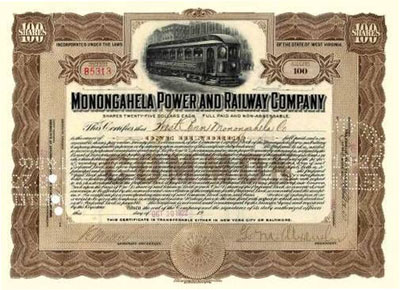

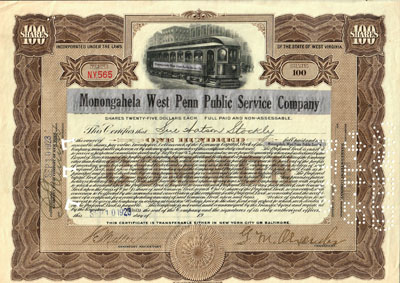

The images below show a stock certificate from the Monongahela Power & Railway Company. The image on the left is dated 1922, a few months before West Penn Power Company formed a separate subsidiary named Monongahela West Penn Public Service Company. That company bought the Monongahela Power & Railway and combined it with another nearby traction company. In order to sell stock quickly, the public service company merely overprinted its own name on certificates of the Monongahela Power & Railway (image on the right.) So, did it cease being a "railway" company? Confusion reigns when trying to answer the question of whether such "new" companies directly operated interurbans under their own names or indirectly through other corporate entities. It is seldom possible to access reliable corporate documents and researchers must rely on derivative sources that frequently disagree with each other. Often later rather than sooner, it becomes obvious that it takes too much time determine whether utilities really operated railways, and if they did, for how long.

|

|

|

Correspondents frequently plead with me to include specific utilities because they ran streetcars for several years. No argument there.

On the other hand, many utilities bought street railway companies for their power generation facilities and abandoned passenger service as quickly as possible. Should such a utility be included in this project simply because it operated a street railway for only a few days. Where would the cutoff be? One day? A few weeks? A year?

It is common to spend an hour or more trying to unravel the rail-related history of a single utility. Even if I spent that time and decided to list a particular utility, how long would it be before other correspondents asked me to include precursor and successor companies? And what should I do about "reluctant utilities" that operated streetcars at losses only because states prevented them from abandoning services sooner?

Utilities that own rail equipment

I have also heard arguments that I should include utilities that never operated street railways or interurbans, but merely own (or owned) vast numbers of gondola cars for hauling coal. That is simply a "rabbit hole" I must avoid. Even if I were to explore that subject, would it be possible to discover whether utilities owned cars or merely leased them?

Let's ask the question of including utilities is a different way

How many railroads would be included in a project titled...

Collectible Stocks and Bonds of North American Utilities

History of utility involvement in street railways

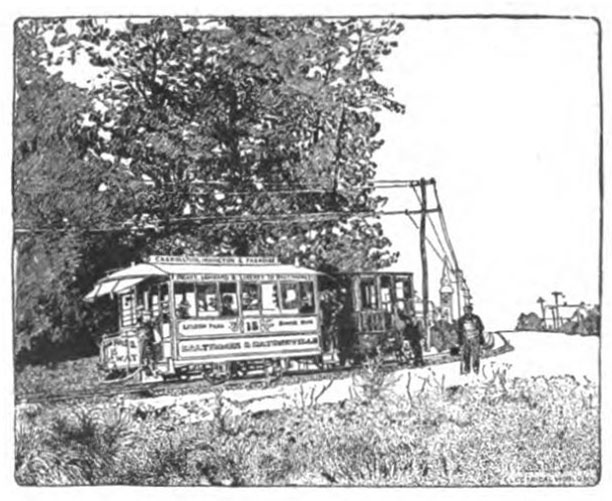

By the 1880s, practically every mid-size and larger North American town and city had streetcar service powered by horses and mules. Electric motors had been around for a half century and numerous attempts had been made to perfect electric haulage with only partial success. In June, 1883, the United States Electric Company displayed a 2,700-pound electric locomotive named "The Judge" at the National Exposition of Railway Appliances in Chicago. Over the course of two weeks, it carried 26,805 attendees in a single car over a 0.3-mile track around the Exposition Hall.

Starting in August, 1884, the Bentley-Knight company ran an electrified streetcar over a stretch of the East Cleveland Street Railway Co for about a year. That effort seems to qualify as the first commercial street railway project in North America.

In September, 1885, about the time the Bentley-Knight project wound up, the Daft Company put another electric car experiment into operation on the Union Passenger Railway in Baltimore. That project used motorized "dummies" that pulled small four-wheel streetcars and picked up energy from an electrified third rail.

More commercial streetcar applications quickly followed, the earliest being:

May, 1886, Windsor Electric Railway (Windsor, Ontario)

Jul, 1886, Appleton Electric Street Railway (Appleton, WI)

Oct, 1886, Port Huron Electric Railway (Port Huron, MI)

Oct, 1886, Highland Park Railway (Detroit, MI)

Oct, 1886, Scranton Suburban Electric Railway, (Scranton, PA)

Apr, 1887, Los Angeles Electric Railway (Los Angeles, CA)

Jul, 1887, Lima Street Rail-Way Motor & Power Co (Lima, OH)

Sep, 1887, Columbus Electric Railway (Columbus, OH)

Oct, 1887, St. Catharines, Merriton and Thorold Street Railway (St Catherines, Ontario)

Oct, 1887, Seashore Electric Railway (Asbury Park, NJ)

Nov, 1887, San Diego Electric Rapid Transit (San Diego, CA)

unk, 1887, Capital City Electric Street Railway (Montgomery, AL)

(Source: The Electric Railway, Fred H. Whipple, 1889, viewable at hathitrust.org)

Some of these early operations were powered by their own dynamos. Others purchased power from municipal and private power and light companies. As the electric street railway industry grew, it was commonly more economical for railways to generate their own electricity. Whether they purchased or generated power, street railways tended to be dependable consumers of large quantities of electricity. Throughout the 1890s and into the first years of the 20th century, railway and utility companies tended to use crossover names such as "XYZ Light & Railway Co." and "XYZ Railway & Power Co."

I doubt that the order of names ever suggested comparative profitability between power and transportation business lines. Conversely, as homes and businesses embraced electrification at an ever-growing pace, I strongly doubt that the sale of street railway and interurban tickets was more profitable than sales of electricity.

By examining the two largest sources of railroad and railway names, we can see that during the first years of the 1900s, many street railways shifted ownership to companies with utility-related names. (See The Trolley and Interurban Directory by Joseph Gross (1987) and Railroad Names by William Edson (1984, 1989, 1993 and 1999.)

From the turn of the century onward, the profits generated by selling power allowed more and more consolidations of utilities. With each new merger, the greater likelihood that reference to "Railway" operations was removed from corporate names. This was especially true after World War I. It seems hard to imagine that companies would have dropped "railway" monikers if profits from passenger haulage had been substantial.

Politics?

Gross' book mentioned above segregates companies by state. Close reading indicates that "pure" utility names (company names that lack reference to railways and interurbans) are found earlier and are more common in some states than others. This may reflect pure happenstance, but it could also reflect political motivations to keep reference to passenger-focused services longer than profits would have otherwise suggested. As we have seen in the habits of the Interstate Commerce Commission, railroad companies often had to wait years before receiving permission to abandon unprofitable and useless branch lines. I suspect some states took the same attitude.

How long did utilities maintain street and interurban services?

I have found that it is dramatically easier to identify utilities that supposedly operated street railways than to identify exactly when they suspended services. Some references are confused because the term "electric trolley services" can be applied to both electric streetcars and electric trolley buses, both of which acquire power from overhead wires.

Although trolley wires created visual sky "pollution," cities tended to prefer trolley buses over fixed-route street railways. They were cheaper to install, easier to shift with demand and created little street disturbance. To avoid confusion, this project purposely avoids the word "trolley" in favor of "streetcar."

I once had a correspondent who insisted that a certain utility belonged in the railroad database because it operated street railways longer than my data showed. I asked him to find proof. After almost a year of on-and-off library work and even examination of corporate records at a museum, he gave up. Like my experience, he found records vague, contradictory, and silent about when the company actually ceased rail service.

Were "transit" companies rail-related or bus-related?

"Transit" is another confusing word with dual meanings. Whenever "transit" is found in a company name after about 1910, research is needed to discover the type of conveyance referred to. Just because a "power and light" company used the word "transit" in its corporate name does not automatically refer to railroading.

Practicality

I started this project because I wanted to track the prices being paid for certificates in the North American railroad specialty. There were a few published references to certificates in general, but not to railroading in particular.

At the time I started, there were no references to certificates issued by companies in any specific industry. Not mining, oil, banking, logging, shipping or anything else. Lawrence Falater followed by project and issued a hardback catalog on automotive stocks in 1997 (American Automotive Stock Certificates by BNR Press), but to my knowledge, no guide for any other single industry has been cataloged since.

If my catalog did not exist and I were looking for certificates from railroad companies, I would definitely look at three works that focus on specific regions; Alaska and Yukon Stocks and Bonds by Dick Hascom, Catalog of Puerto Rico Stocks and Bonds by Dennis Rodriguez and Georgia Railroad Paper by Gary Eubanks. However, even though Lawrence Falater is a friend, I would never expect his book to include railroad certificates. Plainly, railroads are not automobiles.

The same logic extends to utilities. Would any collector of utility-related stocks and bonds look for information in a catalog dedicated to North American railroads? Yes, a collector might look to my project for very early certificates issued by street railway companies which generated their own power. Nonetheless, no one would call those companies "utilities."

If another cataloger were to tackle the task of cataloging securities from utility companies, they would end up with the same problem I face. Where would the definition of utility end and a railroad begin?

While speaking of practicalities, there is one invisible and inviolable fact. When speaking about expanding the project to include utilities, I simply do not have the time.

Time demands into the future

In case anyone is wondering, no, it does not take much time to catalog a new company company nor its certificates. The real consideration is the time that the inclusion of off-topic companies would demand forever into the future.

While some auction companies group similar companies together in their certificate offerings, most do not. Therefore, in order to track prices, I would need to search each non-railroad business type. Each day and each auction, I would need to search for keywords not only in railroading, but in power generation, bus transit, bridges, land, etc. etc. Tracking two specialties (railroading and coal mining) is sufficiently time consuming that I must keep tightly focused on the main purpose of this project.

If ...

... one of my readers wants to take on the project of cataloging collectible certificates from utility companies, let's talk!