Certificate alterations and hand-made certificates

I classify certificates by grouping items of common origins and appearances, starting first with company name, major vignette (or lack thereof), and progressing to less and less obvious features. The task of classifying stocks and bonds shares is similar to classifying plants and animals in the family-genus-species system of evolutionary biology. After all, certificate usages and appearances evolved through time and every company evolved differently. Unlike biology, some certificates shifted from one classification to another during their lifespans. Being made of paper, it was easy for companies to alter, modify, and change terms of certificates to fit changing situations.

My goal as a cataloger is to identify "varieties." Clearly, "varieties" can mean different things to different people.

In my system, varieties are groups of certificates that share identical appearances and purposes. The definitions of varieties must be sufficiently flexible to allow for differences in the ways certificates came into existence. Finally, definitions need to allow tolerance for variable sizes, ink colors, paper colors, serial numbers, and a host of the other differences we encounter.

It would be relatively simple to determine varieties if we had examples of all certificates just as they came off presses. Even if that ideal existed, we would still encounter problems with classification because companies often changed rules as they shifted to meet business conditions. Companies frequently changed par values and capitalization amounts. Unless they were unsuccessful and bankrupted quickly, companies continually changed corporate officers and trust companies. It was not uncommon for companies to change certificate denominations for transitory purposes. If they avoided immediate failure, every company changed corporate names at some point. If companies responded to changes by merely altering certificates instead of printing new ones, we would inevitably need to decide which changes created new varieties and which did not.

Classifying altered certificates can be challenging and subject to disagreement. I want to be as consistent as possible as well as minimize overly complex, flyspeck varietization. Consequently, I created a rule for deciding the kinds of altered certificates that deserve separate variety numbers:

Acceptable varieties

Certificates altered as a result of official decisions at the level of boards of directors are considered separate varieties.

... and the corollary ...

Certificates altered by non-board actions are not considered separate varieties.

... furthermore ...

Certificate alterations caused by individual, minor, incidental, accidental, or non-corporate decisions are ignored for varietization purposes. Those include changes by clerks, banks, trust companies, unrelated companies, states, counties, and courts. Those kinds of changes were out of the control of issuing companies.

Following is a collection of various certificate alterations you might encounter.

Handwritten, typewritten and mimeographed certificates

Image courtesy of Corey Phelps

Hand-composed certificates generally constitute the very earliest evidence of companies. They tend to be unique or nearly unique. Once signed, dated and stamped with corporate seals, these handmade certificates were legally binding documents, no different from professionally engraved and printed certificates. Only a small number of such certificates survive and all are cataloged as distinct varieties.

(Image at right is an entirely handwritten certificate #1 for a $40,000 bond from the Keosauqua & South-Western Railroad Co payable to Ransom R. Cable.)

Generic form certificates with handwritten, typewritten, or locally printed company names

Image courtesy of Max Hensley

Generic certificates were commonly printed by lithographing companies. They were probably sold on a wholesale basis to local print shops and on a retail basis through stationery stores. Generic certificates are still used today.

Hundreds of railroad companies might have used the same generic certificate design, but seldom would any single railroad company have ordered more than 50 to 200 generic certificates. Once sufficiently successful, most startup companies either merged with larger companies or turned to custom engravers to produce subsequent certificates. Regardless of how company names might have been added to generic certificates, all are considered legitimate varieties.

(Image of handwritten name of Brownsville Street Railway Co on generic certificate created by an unattributed printer.)

Modifications to corporate names

Image courtesy of Vern Alexander

When companies merged or consolidated with others, it was relatively common for them to use old certificates temporarily for the new company .While companies normally ordered new certificates quickly, they often had to alter company names on old certificates if they sold shares before new certificates arrived. Hand-altered certificates are seen rather frequently. Rubber-stamped names are also somewhat common. Another method, seen only occasionally, was to have printers overprint new corporate names on old certificates.

Transitional name changes also fall into this category. Those are certificates which were issued prior to corporate changes and then changed some time AFTER issuance. It appears that many transitional certificates were probably not changed until they made their ways through the clearing house system. Stockholders or brokers probably made a few name changes on their own. Regardless of origin, transitional name changes represent official board decisions and clearly qualify for new variety numbers when found. Certificates with name changes are always listed under new company names. Note also that certificates with transitional name changes may be the only evidence that certain companies ever existed.

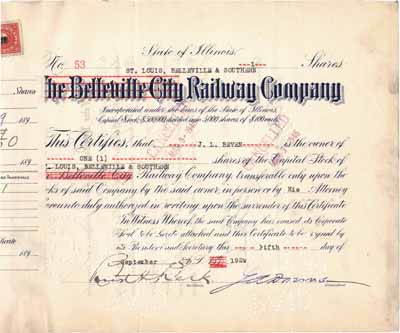

(Image of stock certificate of The Belleville City Railway Co changed to St Louis Belleville & Southern Railway Co)

Altered par values

Image by Terry Cox

Company share prices tended to rise as companies became more successful. The downside of those rising prices was that expensive shares frequently became less attractive to small investors. It was fairly common practice to "split" stock once prices remained over $100 per share for extended periods.

Companies often split their stock by lowering their shares' official par values and then issuing more stock. In other words, if the par value of a company's stock was $100 per share, but shares had been trading for $150 in the open market, that company might decide to split its stock "two for one." The company would then trade two shares of "new stock" (at $50 par) for every share of "old stock" (at $100 par.) New shares would trade initially on exchanges for about $75 and then rise or fall from there. "Two for one" splits are common, followed by "three for two," "three for one" and occasionally other schemes.

Companies had several reasons for changing par values and the practice became common after 1950. Companies generally printed new shares ahead of time and had them ready to issue whenever they announced stock splits in the press.

Certificates with altered par values are scarce on railroad stock certificates. They are seen more frequently on certificates from small coal companies. This project considers all certificates with altered par values to be distinct varieties, transitional between old and new certificates.

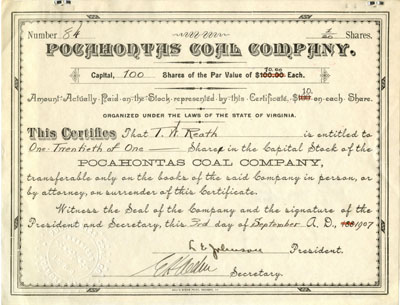

(Image of a stock certificate from the Pocahontas Coal Company of Virginia with par value changed from $100 to $10 by hand upon issuance in 1907. After repricing shares, this company had a capitalization of only $1,000.)

Altered capitalization amounts

Images from several collectors.

"Capitalization" is considered the sum of the total number of authorized shares times official par value. As successful companies grew, either by normal business expansion or by acquisition of other companies, boards frequently changed the number of outstanding shares by increasing corporate capitalizations. Although the reasons are more diverse, it not terribly uncommon to see decreased capitalizations on certificates.

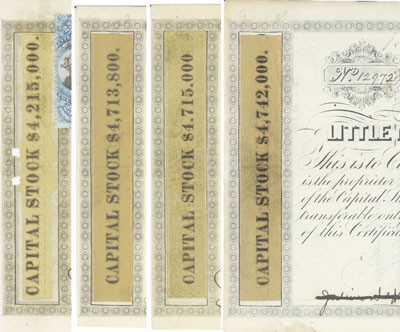

The most common changes to capitalization were handwritten followed by typewritten and rubber-stamped changes. Occasionally, strips of silver or brass-colored paper was applied over old capitalizations which then formed a substrate for overprinting. Certificates from the Little Miami Railroad are frequently seen with brass-colored overprints. (Four variations from several contributors shown at right.)

While handwritten capitalization changes are fairly common, most companies are represented by only a few examples. The reason is not known, but it appears clerks may have grown bored with the alteration process and gave up after short periods. Capitalization changes are considered separate varieties.

Alteration of pre-printed denominations

Image courtesy of Holabird Western Americana Collections, LLC.

Larger companies often authorized the engraving and printing of specific share denominations, particularly 10-sh, 25-sh, 50-sh and, 100-sh. Companies could never predict the number of certificates might be required in any particular denomination, so it is not uncommon to encounter alterations of pre-printed denominations. Some alterations were handwritten and some were accomplished by professional printers. It is the policy of this project to ignore handwritten changes to pre-printed denominations because they probably reflect convenience, frugality, or laziness instead of board decisions.

Conversely, alteration of pre-printed denominations by silvering and overprinting is thought to represent formal corporate decisions to spend money for that purpose. Hence, printed alterations to pre-printed denominations are considered separate varieties.

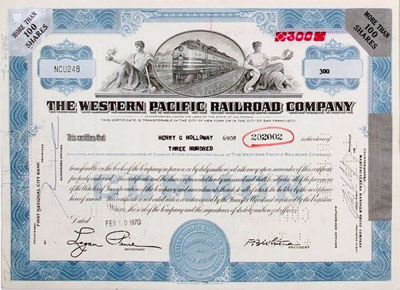

(The image at right shows an alteration of a "less than 100 shares" stock certificate of The Western Pacific Railroad by "silvering" to "more than 100 shares.")

Altered certificate types

Image courtesy of Coleman Leifer

The changing of certificates from one type to another (such as common to preferred) is considered to represent formal decisions at managerial levels. Such changes created legal ramifications because they represented different types of securities and those securities could be bought and sold like any other asset. Each version is considered a separate variety regardless of whether changes were made by hand, typewriter, rubber stamp, or overprint.

(Image of a portion of a capital stock from the Duluth St Cloud Glencoe & Mankato Railway Co changed to the "First Preferred" type by rubber stamp,)

Altered trust company and registrar names

Image by William Knadler

While the change of one trust company to another may have represented board decisions, it is just as likely that name changes were brought on by changes in trust companies, savings and loans, and investment banks. Without time-consuming research, it is impossible to know why trust company names might have changed. Moreover, such changes had no effect on the sale or legality of underlying stocks, bonds or other documents on which those names appeared. This project generally ignores changes in the names of trust companies and registrars.

There are few extraordinary exceptions where certificate designs changed at the same time as trust or bank company names. In those rare cases, it might be easier to spot and describe changes in the names of trusts or banks than to over-describe subtle design differences.

(The image shown represents one of several slight variations of a popular certificate design from the Cleveland & Toledo Rail-Road. The company issued this certificate design in two series, each with different pre-printed dates. All the principal designs elements persisted, but there were slight changes in the text that are most easily identified by the transfer company name at left. The example shown was transferrable at the Corn Exchange Bank. Other variations include Wells Fargo & Company, Ohio Life Insurance & Trust Company, and the Farmers Loan & Trust Company. Since it is difficult to describe textual changes, this project turned to more obvious differences in trustee names.)

Altered pre-printed dates

Image courtesy of Dr. Thomas O'Shaughnessy

It is highly common to encounter handwritten and typewritten changes to pre-printed portions of dates. It was very common for clerks to overwrite the last one or two numerals of pre-printed dates in order to date certificates in later decades. Such date changes are very numerous on stock certificates, but had no effect on certificate viability. Alterations were made at the clerk level and are therefore ignored as variety changes.

(Image of an '185- pre-printed date on a stock certificate from the Steubenville & Indiana Rail Road altered for issuance in 1860,)

Facsimile signatures

Images courtesy of Kevin Nesbitt

Appointment of presidents and other high-level employment positions were made by boards of directors. Yet, no matter how important those appointments might have been, changes in personnel were nothing more than normal and ordinary business decisions common to every company. This project ignores all president, treasurer and secretary names in establishing varieties.

20th century certificates frequently show differences among facsimile signatures of corporate officers. It is true that certificates with various signature combinations were prepared and printed separately, sometimes five or ten years apart. However, each change still represented ordinary day-to-day operations of companies. For that reason, I consider variations in pre-printed corporate signatures to be ordinary "course of business" variations, not rising to "variety" status.

(Images of Canadian Pacific Railway certificates with the same secretarial and presidential signatures,)

Overprinted changes to bond terms

Image courtesy of Deborah Woody of Hollins Certificates

Bonds are official, contractual obligations between companies and debt-holders (people who lent money to companies and received bonds as evidence.) Unless directed by courts, both lenders and borrowers had to agree any time there were any changes to terms of agreements related to the repayment of debt. Official corporate changes to bonds are rare.

On the other hand, numerous overprints are known on bonds and occasionally stock certificates where repayment or ownership conditions were altered by courts during bankruptcy proceedings. The most common changes to bonds indicate amounts of partial repayments made to bondholders after dissolution or sale of assets. Many of those alterations have been erroneously recorded as cancellations by sellers. Because those marks often recorded partial bond repayments, they constitute a form of partial repayment of debt. Nonetheless, bonds still retained partial value after the last overstamp, so we cannot consider them officially "cancelled."

Overprints and overstamps created by court actions were legally binding and "official," but they were made by courts and not boards of directors. This project does not consider them separate varieties.

The only exception, and one that is highly rare, are overprints made in response to the "abrogation of the gold clause" in June, 1933. Federal law prevented repayment in gold coinage and therefore changed gold bonds into lawful money bonds. This project considers them separate collectible varieties.

(Image above shows a printed overstamp that made a partial payment on the entire Delaware & Hudson Company bond issuance. By itself, the overprint would not constitute a new variety. However, the bond itself was revalued the bond from $5,000 to $4,500 and therefore warrants a separate variety number.)

Colored seals

Image courtesy of Greg Alexander

Prior to the last few decades of paper certificate issuance, most states required impressions of corporate seals into stocks and bonds as conditions of legitimate issuance. The impression of corporate seals was variably accomplished by the attachment of paper seals, foil seals, and none at all. Decisions about the application of seals seems to have been unofficial and carried no particular importance. This project ignores differences in paper or foil seals in the process of determining varieties.

(Most Woodruff Sleeping & Parlor Coach Co bonds show a dark blue paper seal in the bottom left corner. A smaller number of seals were lime green in color and appear primarily among higher numbered certificates. Because of the randomness of the applied colored seals, we must assume they had no meaning other than available supply.)

Differences in embossed corporate seals

Images courtesy of David Adams

There is a question whether differences in embossed seals would be cause for creating different variety numbers. As an observer and cataloger of the hobby, I must conclude, "yes." Corporate seals are very much official requirements of incorporation. Changes in embossed corporate seals must, therefore, represent board decisions at the very least. Different seals theoretically should equate to different varieties.

There is, however, an major problem in using embossed seals to determine varieties. Embossed seals are impossible to see except in the best, highest-resolution, specially-staged photographs. I have never seen a seller mention details of embossed seals. If I cannot see corporate seals in an overwhelming majority of the certificate population, I must ignore them.

In November, 2021, a collector alerted me to variations he had spotted in certificates from a small West Virginia railroad. I was fortunate to have several good images of certificates from the Loop & Lookout Railroad and together we unearthed a curiously complex organization among the very small number of certificates issued:

- Two different variations of company names are known (with and without ‘The'.)

- Two different places of business appear on seals (Evenwood, WV and Rainelle, WV.)

- Two different incorporation dates appear on corporate seals.

- Three different corporate seals designs are known (two with ‘The’ and one without.)

I currently list two different varieties (with and without the words 'The' in the corporate name), but one could make the case for four different varieties based on various combinations of features. Unfortunately, this would be problematic because images of acceptable clarity are NOT available for the majority of potential sub-varieties.

Changes to places of issuance

Image courtesy of Pete Angelos

It is not uncommon to see hand and typewritten changes to locations where certificates were issued, especially on stock certificates. Such changes could have represented board decisions, but they could have equally represented changes by clerks and brokers. To my knowledge, printed place of issuance never carried legal ramification. As long as certificates were issued from the states where companies were incorporated, issuance from different places within those states was immaterial. Changes to places of issuance are ignored in determining varieties.

Again, like practically every other "rule of thumb" in this hobby, coincidental exceptions have appeared that could not be ignored. Shown is an example of a popular certificate design from the Marietta & Cincinnati Rail Road. Early examples of this "second class preferred" stock certificate were issued from Chillicothe, Ohio. Later examples were issued from Cincinnati.

In normal cases, the variable places of issuance might be an interesting detail to a handful of collectors, but I would ignore for cataloging purposes. In this example, however, later certificates are grossly similar in appearance but display several less noticeable differences. The easiest way to identify the different varieties is by the handwritten place of issuance.

In conclusion

This project ignores certain alterations that probably were not the result of corporate actions, but by:

- convenience, frugality, laziness, or impatience

- courts or non-related companies

I understand that some collectors might disagree. Some of my varieties might seem too microscopic or too broad. It is reasonable to ask how they can tell whether decisions were made at the board of directors levels or elsewhere in organizations.

We will never know who made decisions at most companies. The vast majority of corporate records are either lost or effectively impossible to find. However, corporate laws are grossly similar from state to state. I suggest that certain types of decisions could have been made only at the highest levels. Such decisions include changes to par values of shares, capitalizations, corporate names, and types of bonds and shares issued. All those decisions determine how much money a company might have raised by selling shares and even how easily it might have been to sell securities.

Decisions about alterations of less importance could have been made at board levels, of course, but generally were made at lower levels. It seems unlikely that a board would have voted on what color of paper seals to use or where to scribble the word "preferred."