Imported from: Google Blogger site

Original publish date: July 27, 2017

Terminology - "coupon bonds" versus "bearer bonds"

Are these terms equivalent? Well-l-l-l. Not really.

First off, I want to make it clear that I am talking about corporate railroad bonds. I am NOT talking about U.S. Treasury bonds and related securities.

Read practically any coupon bond and you will usually see that some company promised to pay a bank or individual OR BEARER a sum of money on a specific day. Why this phrasing?

Generally speaking, the engraved text on bonds specified the company would have given a "mortgage" on its assets to one of more wealthy individuals or a large bank in return for money. Along with the mortgage or other contractual agreement would have been a large stack of bonds.

It is crucial to understand that a "mortage" is NOT a loan. A mortgage is a security agreement. It says that the company (the borrower) will give specific assets to the lender(s) if it fails to pay interest or fails to repay principal as agreed.

The bond at left is a $50,000,000 loan. Theoretically, the Cleveland Cincinnati Chicago & St Louis Railway Company would have given the Mercantile Trust Company a mortgage and $50,000,000 in bonds. In return the Trust Company would have given the company several million dollars right away, but NOT the entire $50 million. The Trust Company would then have attempted to sell CCC&StL bonds to its customers. If successful in selling bonds, it would have subsequently lent the company more money over the ensuing months and years.

That does NOT mean all of the $50,000,000 in bonds were ever sold. That does NOT mean all, or even any, any of the bonds were sold for $1,000 each. That does NOT mean the railroad company ever received the whole $50 million it bottowed. Remember, it was the Trust Company assuming risk and wanted to be paid for that service!

For ease of selling, this bond was issued to the "Mercantile Trust Company of New York, or bearer." Whoever bought bonds from the Trust Company became owners the moment the bonds were handed over. No muss; no fuss.

Obviously, bearer bonds were wonderful assets when they needed to be sold quickly. Only buyer and seller were involved. Redeeming coupons for periodic interest payments was equally easy because they too were bearer instruments. Whoever turned coupons in for redemption were the ones who got paid.

However, bearer bonds and their attached coupons were terrible assets in the event of any kind of loss. Whether it was fire, flood, earthquake or theft, bearer bonds were rarely replaceable once lost.

The obvious solution was to register bonds with companies. Once a bond was registered, every sale needed to be recorded and that required some chunk of company time. But, at least the bond was safe.

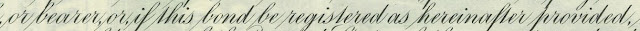

The text of most bearer bonds issued from the 1870s onward allowed changing from bearer to registered status. For instance, the text of the CCC&StL bond clearly said, "or, if this bond be registered as hereinafter provided."

In the text that followed, the bond indicated that the bond, "may at any time and from time to time, be registered."

Does that mean what I think?

Yes, bearer bonds could be registered to a specific owner and then registered to a different owner and then registered to still a different owner. Maybe even back and forth between registered and bearer status. Specifically, the text on this bond says, "until registration is made to bearer."

What happens to the coupons if a bond is registered?

Even though bearer bonds might be registered, the coupons could have stay with the bonds or they could have been removed. Whatever the owner or the company preferred. Specifically, "the owner of record may surrender all unpaid coupons hereof."

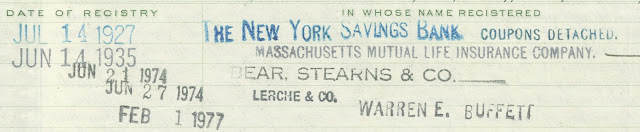

This particular bond was issued in May, 1893, shortly before the great Silver Crash. That does not actually mean the bond was sold to an investor that day. It might have remained unsold for days, weeks, or even years. The registration panel on the back shows the bond retained its status as a bearer bond for 34 years, at which time the New York Savings Bank had the bond registered in July, 1927. At that time, the Savings Bank decided to surrender the remaining 165 coupons in order to be paid regular interest directly by the company. The transfer agent made note of that fact by stamping the bond, "Coupons Detached." (See the first line below.)

The New York Savings Bank then held the bond through the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the worst years of the Great Depression before ultimately selling it to the Massachusetts Life Insurance Company in 1935. That company held the bond for the next 39 years before selling it to Bear, Stearns in 1974. Bear, Stearns for only a few weeks before selling it to Learche & Co.

Three years later, the railroad company was swept up in the large Penn Central bankruptcy and was being transferred to Conrail. At that time, the bond then went under the ownership of Warren Buffet who held it for 20 months at which time it permanently cancelled on November 3, 1978. Buffet purchased the bond at a time when investors were arguing that railroad bonds such as this were either highly over-valued or high under-valued. It's hard to guess what Buffet might have paid, because this was a time when Conrail was negotiating how much to pay Penn Central bondholders. I do not know the outcome, but I seriously doubt Buffet lost any money.

What about an example of the opposite direction in registration?

I have only have one example and this is one of 999-year bonds of the Elmira & Williamsport Rail Road Company issued during the Civil War. It originally had 100 coupons attached. The engraved text says that the bond was issued to "Richard H. Downing, or assigns."

A registered bond with coupons? Hmmm.

These bonds are entirely silent about the meaning of the word 'assigns.' There is a registration panel on the back which very similar to the CCC&StL bond. The E&W bond, however, shows absolutely no evidence of ownership for a century until it was transferred "to bearer" on Dec. 4, 1963.

Who had the bond during this period? Who cashed in all the coupons? All we can do is make some logical assumptions. We can assume that:

- More than one person or company had possession of this bond for a century.

- Those investors or companies collected about $5,000 worth of interest during that period.

- For some unknown reason, some legal owner expended the effort to officially convert the bond to bearer status in 1963.

- There are absolutely no transfers recorded on the bond in the intervening period between 1863 and 1963.

- It seems unlikely that someone presented proof of legal title every time they redeemed coupons, and therefore acted like "bearers."

Until corrected, I must assume that the word 'assigns' was interpreted as 'bearer' for the period between 1863 and 1963. For all intents and purposes, this coupon bond seems to have been a bearer bond for its entire lifespan. Or at least until September 3, 1982 when Congress enacted the Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act of 1982 (aka TEFRA) that required that securities be registered in the name of the owner.

In conclusion, it appears that most coupon bonds had the ability to transform from bearer bonds to registered bonds and then back again. Secondarily, some old 'registered' bonds may not have been treated the same way as later registered bonds. Finally, the terms 'bearer' and 'registered' really involve the idea of protecting an investment from physical loss much more than the concern over how interest was going to be paid on that investment.

To which I say, it is no wonder beginners are sometimes stymied by bonds!